Like most other Gen Z nerds, I went through middle school with my nose buried in The Hunger Games and its sequels, reading and rereading until I’d deemed every important detail sufficiently memorized. Then I went to high school and hit the “gifted kid burnout” portion of my life and reading for pleasure no longer seemed like an option, let alone a priority. But the release of the movie adaptation for the prequel to the series, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, awoke something in me a decade after my initial obsession and I got my hands on a copy of the book as soon as I could. What I left my reading with is a solidified understanding of the author Suzanne Collins not only as a consistent and intentional character writer, but also a historian.

Songbirds

The series takes place in Panem, a small nation formed after an unspecified event leads to the destruction of most of North America, or at least any habitable areas. The remaining land is divided into thirteen districts and a Capitol, where the rich and powerful reside. It is due to this divide that the thematic conflict of the series takes place–a continual struggle for the redistribution of power. Because the setting is America rather than a country that doesn’t exist, Collins has not been worldbuilding so much as applying our history to a fictionalized time in the future. As the reader, we enter the series with only a vague framework of the social environment and main event:

Long ago the districts waged war on the Capitol and were defeated. As part of the surrender terms, each district agreed to send one boy and one girl to appear in an annual televised event called, “The Hunger Games.” The terrain, rules, and level of audience participation may change but one thing is constant: kill or be killed. (suzannecollinsbooks.com)

Ballad highlights the tenth occurrence of these Games and while there are many parts of this addition to the series that expand upon the original trilogy, I was most taken by the character Reaper Ash. A member of the group of children selected to fight, he’s one of a few canonically Black participants across the books, as confirmed by his opening description as “a tall boy with dark brown skin and patched burlap clothing” (The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, Suzanne Collins 40). Reaper’s introduction includes his alleged murder of a Peacekeeper (this universe’s equivalent to the police) in District Eleven which, along with his stature and generally aggressive demeanor, solidifies him as a top contender amongst smaller and less violent competitors. After entering the Arena in which the Games take place, though, he seems to release any violent tendencies nearly completely, and this is where my fascination is rooted. The information we as the reader are given about his personality and motivations assert him as a true activist whose approach clearly references that of the greats; Reaper is educated, compassionate and aware of the power of subversion.

It’s important to know that in Collins’ world the act of performance either directly delivers exposition about a character’s life or communicates an overarching personality trait to the audience. In Reaper’s case, he allows the Capitol and the public of Panem to believe that he’s a thoughtless brute because it serves his purpose–survival. While there are moments where he seems to exhibit true anger, once the Games begin he neglects to enact even the violence sworn onto his fellow tributes as they prepared, having claimed intentions to be the last left standing and “take revenge on the Capitol” (Collins 188) to make it up to the others.

Inside the venue he actually spends most of the time in isolation, seemingly changing his mind upon entering and making no concerted efforts to take out any of his competitors. He proves himself to be capable of some level violence in his early intimidation of Capitol citizens, but he seems hesitant when it comes to those being subjected to the same horrors as him. What he does do, though, is create a display that forces the government to directly confront their atrocities in the same way he is being made to do in the Arena. Using the privilege provided by his physical advantage to move freely, he creates an unavoidable reminder that no matter how much of a spectacle it’s made into, this event is kids killing kids. After being in hiding for a while, Reaper emerges to the carnage from the first large battle:

He seemed unable to make sense of the scene before him…After walking around them for a time, he lifted Lamina up, carried her over to where Bobbin and Marcus lay, and arranged the three in a row on the ground…Once he’d neatly lined up the others, he swatted at the flies that had gathered. After pausing a moment in thought, he went back and cut off a second piece of the [Panem] flag, draping it over their bodies. (Collins 280)

His mourning ritual and respect for the dead being shown on such a large scale is a direct slap in the face to those in power; they rely on their portrayal of the districts as animals for the continued success of the Games and he knows that, so he creates an undeniable display of their humanity. Following this rebellion, he takes another scrap of the flag as a cape and recedes to a corner inaccessible to the other tributes, biding his time adding to his graveyard when necessary and maintaining a hunger strike in protest of the bourgeois’ support. Reaper dies as himself, with integrity, rather than as a simplified caricature and serves the community along the way.

The motivation behind his refusal to fight in the Arena is never confirmed, but I believe there to be two options–either he was telling the truth and had intended to win but was deterred by the reality of killing his peers, or he was temporarily making himself fit the mold he’d been pushed into, banking on the subversion of expectations to be sure that his time on display would be significant in its pacifistic nature. Whatever the true reasoning for his pivot in the arena, it’s clear that Reaper was early in a long line of tributes who went into the Games with the intention of doing what they could to end them. He created his own form of dissent with the resources he had access to, demonstrating that the solution at this point may not be to fix or even overhaul the existing system that fails to serve us, but to create our own. In this way he’s much like the most efficient activists of the Civil Rights Movement–young, creative and motivated.

SNCC (“snick”)

The most effective activism of any movement in history has both been performed by those who are well educated on the issue and included a focus on the continued spread of education amongst the disadvantaged. The United States’ Civil Rights Movement is my personal favorite example of this, as so much of the mission both focused on education and was revolutionized by students. In early 1960 the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was created in Raleigh, North Carolina as several young sit-in organizers from around the South made the decision to unify their desegregation efforts.

Bolstered by the support of Ella Baker, SNCC was formed and grew rapidly from a few sit-ins to a full operation with staff and a headquarters. By the next year they had shifted their focus slightly, adding the position of “field secretaries” who aimed to register more Black voters by providing access to the information and/or forms needed to participate in an election. The intention of voter registration as a community effort is to give the people more control over their governmental representation, and even today often takes the form of canvassing underserved neighborhoods on foot. Because of the interpersonal nature of the work, this also had the unintended benefit of recruiting more SNCC members. Through the early sixties they continued to register and prepare Black Southerners for voting despite the rising threat of violence in Black spaces and increasingly convoluted advice of the government before expanding the goal and functions of the organization.

With the aid of more experienced educators and activists, by 1965 the group’s goals had become much more pointed. SNCC wanted to get more Black people into positions of power themselves, as obstacles to their registration efforts were beginning to arise from even those who had previously encouraged them and hardly any white politicians have ever actually been in the interest of serving the people. Stokely Carmichael in particular aimed to create a new Black political party completely separate from the white majority and found a willing partner in John Hulett, an organizer local to Lowndes County, Alabama. The two met in March of ‘65 when a SNCC group participated in the march from Selma to Montgomery and brought the two groups together to create the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, with a black panther as its chosen motif.

Hulett described the black panther as “vicious,” stressing that “he never bothers anything, but when you start pushing him…then he comes out and destroys everything that’s in front of him” (Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP), snccdigital.org). It’s with this selection that we start to see themes of subversion and adaptation as a necessary part of utilizing one’s power emerge in the movement as a whole. By the start of the next year the LCFO had grown enough in size to become the first official Black political party and their strategy, along with their symbol and its accompanying philosophy, quickly impacted the way that all activism was approached with a scope far beyond just Alabama.

Use of the panther as a symbol became more widespread following the publicity garnered by the Conference on Black Power and Its Challenges organized by UC Berkeley’s Students for a Democratic Society on the 29th of October, 1966; with Carmichael’s contribution, the accompanying program featured an image of the animal prominently and the conference’s success brought nationwide attention. In August of the same year a patrol group had been created to combat police brutality occurring in Los Angeles and utilized the panther as a marker on their vehicles, broadening the reach quickly through visibility. By September “organizing had begun under the black panther symbol across the country…including independent efforts in Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, and New Jersey” (Black against Empire, Bloom and Martin, Jr. 43), with Harlem and West Coast chapters of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) transitioning to follow the model of the LCFO and starting their own Black Panther Parties. Having already been well established on both coasts, RAM’s endorsement of the platform led the Panthers to grow to the scope and impact they’re now referenced with.

The most well known Black Panther Party was formed and named in Oakland, California that same September. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, both community college students at the time, bonded over their shared revolutionary views that exceeded the intensity of any established organization and moved to fill the space they felt had been left empty. Together they founded a group that outright “rejected the legitimacy of the U.S. government [and] saw black communities…as a colony and the police as an occupying army” (Bloom and Martin, Jr. 2). The two dedicated their free time at this point to the local chapter of RAM but were finding themselves on the outskirts as leadership became unsettled by their militant viewpoint.

Already involved in community work and increasingly unpopular amongst their peers, the pair followed in the lead of both the Harlem and West Coast RAM organizers and established their own Party in Oakland. Named in its entirety as the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, Newton and Seale’s chapter quickly gained the attention of young Black people who had been seeking a more confrontational approach to liberation. They grew from a relatively small operation mostly local to California to operating in nearly 70 different offices across the States in two years and quickly became a threat to the system in place. The way that the Panthers operated was new in its logistics and leadership configuration and, more importantly, in the generally unified and staunch nature of their stances as an organization.

While the party maintained from its inception that education was one of the most important of the resources being denied to the Black community, a shift to the individual leadership of Seale following Newton’s arrest brought about a new emphasis on the matter. The Panthers operated on the basis of a 10-Point Program, the fifth of which read…

We want decent education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present-day society…We believe in an educational system that will give our people a knowledge of self. If a man does not have knowledge of himself and his position in society and the world, then he has little chance to relate to anything else. (Bloom and Martin, Jr. 71)

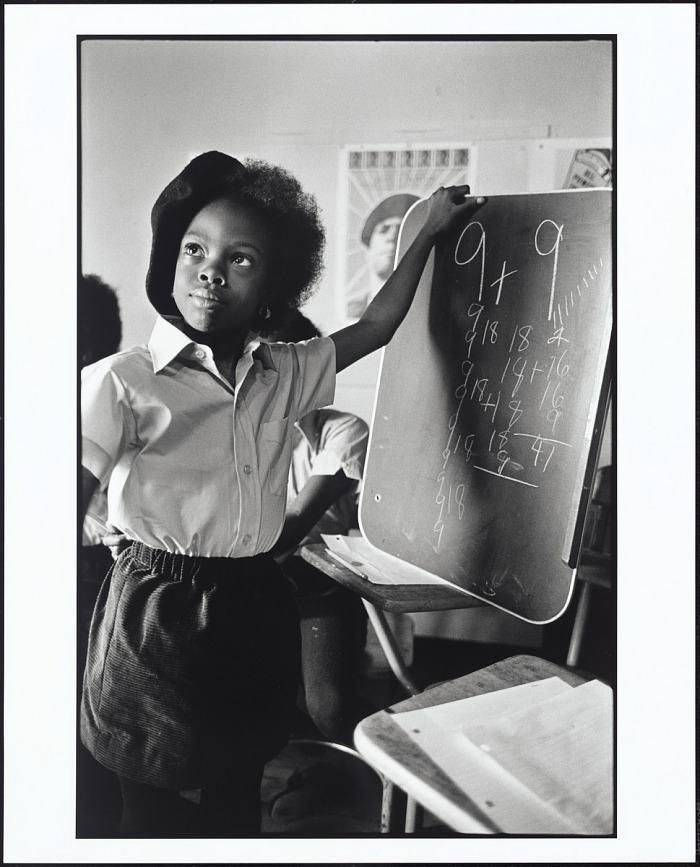

Because the Black population was unable to place any level of trust in the education system in place, the Panthers made moves to create their own. Though there were several steps towards desegregation made through Supreme Court cases in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the damage done by these policies continued to manifest, especially in educational settings. The solution created by the new independent party was first to do what they could to help the children already in these lackluster schools make the best out of it, followed by the creation of their own system entirely.

Education as a Liberatory Tool

The Free Breakfast for Children Program, one of the most significant liberation efforts executed by the BPP, was created and launched in September 1968 and had such massive success and community support that “by November [of the following year] the Party reported feeding children free breakfast daily in twenty-three cities across the country, from Seattle to Kansas City and New York” (Bloom and Martin, Jr. 182). This was direct action in the interest of making education easier on the children; it’s proven to be more difficult to learn when undernourished and Bobby Seale and his constituents prioritized providing the tools necessary for the students to learn effectively. By ‘69 it was the largest operation being run in the movement, with most branches enacting the program for some length of time, though some were less consistent than others. In an escalation that mimics the origins of the Black Panther Party itself, the Free Breakfast program was expanded into the establishment of completely independent Black schools as leadership lost hope for change within the public school system.

Inspired by the work of Septima Clark and the freedom schools of Mississippi history, the Panthers decided to build their own school system. These liberation schools were staffed with Black educators and dedicated to “the inclusion of black perspectives, experiences, and knowledge in the formal and informal school curricula” (Bloom and Martin, Jr. 192). The first showed up in Berkeley in June 1969 as a supplementary program and later expanded to full school operations, accompanied by nine other community schools across the country. The most famous is commonly known as the Oakland Community School (originally named the Intercommunal Youth Institute), which operated successfully from 1971 to 1982, outliving the Panthers as an organization. Under mostly female direction and leadership, the elementary school served hundreds of children from 2-11 years old over its lifetime.

Director from 1973-81 Ericka Huggins has placed this effort in the larger context of activism, describing it as “no less significant than women who organized and educated black and poor communities in the 19th and early to mid-20th centuries…the OCS administrators and faculty saw the dire need for quality education and stepped forward to create change in educational conditions for youth of color” (The Oakland Community School: A BPP Community Survival Program, Ericka Huggins 2-3). Providing languages, arts, extracurriculars and regular meals along with a comprehensive and Afro-Centric history curriculum, the OCS posed a huge threat to already wary national leadership with the undeniable size of its impact.

In an interview recorded in 2007 Huggins described a typical day at the school, stating that the children were always fed and emotionally checked-in on before classes began. “We did ten minutes of exercise and then we went to class…The children just felt completely cared for,” (An Oral History With Ericka Huggins, Fiona Thompson 84-85) she elaborated. Offering three square meals a day and an open door policy in the interest of tending to the students’ mental health needs, even the programming of their time outside of the classroom was revolutionary. The level of education and care provided to Black children at OCS made waves not just because it benefited the community but because it was nearly unprecedented in the U.S. for public and private schools alike. The structure remained similar to that of the typical elementary school, but the information that the students were able to access and choose between heavily referenced models from alternative and international educators. She went on to explain several of the practices employed:

Project Seed was this innovative math tutorial [that] taught algebra, algebraic thinking, problem solving, to third, fourth, and fifth graders…the school taught the children how to do this Korean finger-counting called Chisenbop…and then I taught poetry writing to the children. After I began working with my spiritual teacher, he encouraged me to teach the children meditation…So the school culture created itself through our intention to love the children, to teach them how to think, and to have them become global citizens. (Thompson 85)

In her words, the administration later learned that much of what they had created aligned with the beliefs of both the National Association of Alternative Schools and Chinese educators, who were admired by the teachers of the Party but not intentionally referenced until after they’d been operating for a while. Further inspection of both of these groups only confirmed that they were on the right track. Due to the revolutionary nature of the information being freely provided to the Black youth in liberation schools, they only bolstered the government’s view of the party as a negative force in society, and the reach of the Oakland Community School in particular was growing seemingly exponentially. It maintained a full waitlist of children of all ages for most of its lifespan and the popularity as well as the newness of their teaching philosophy garnered an amount of attention that was despised by FBI leadership and the administrations in place at the time. The Black Panthers were already seen as “purveyors of anti-American and antiwhite propaganda” (Bloom and Martin, Jr. 192) and therefore a threat to the supposedly peaceful state of things, so their educational efforts were considered a part of that propaganda.

While the Intercommunal Youth Institute survived many iterations and the downfall of the Party as a whole, it did eventually close in 1982, cracking under “the cumulative impact of government surveillance of the BPP and the decline in [the Party’s] leadership,” (Huggins 9) along with an unfortunate decrease in funding. The impact left on the culture of education in America, though, cannot be ignored. The faculty’s approach to gathering and disseminating information was free flowing and individualized to fit the students in a direct contradiction to what occurred in public schools then and what continues to occur in them now. Liberation schools were targeted because they existed outside of the government’s sphere of control–what was being taught in them was out of the government’s control. The goal of the president and FBI was to somehow gain control over the words of Black activists and these schools made them feel like they might be fighting a losing battle. They understood that an uneducated population is a docile one and a lot of effort went into attempts to make information more difficult to access; when the uneven distribution of knowledge is a crucial part of maintaining the power system in place, its acquisition basically necessitates dissent. Full cognizance of the history and functions of this country is and always has been what its leaders fear the most.

The Point

I chose now to talk about Suzanne Collins because with The Hunger Games back in the zeitgeist, it’s crucial that we all understand that the work that she’s done in the series is deeply informed by our country’s history. While it’s a fantastic work of fiction, it’s grounded in a multitude of references to real events and activists that we should all have the tools to fully comprehend. I chose now to discuss the leadership of students and educational work in the Civil Rights Movement because I think they need to be prioritized among these reference points. The stress placed on learning by groups like the Panthers is relevant to the struggle we face now–a profound corruption of our educational system by way of several incompetent administrations and intentional interference with any information that is allowed to the general population.

In recent years there have been several obvious moves made federally in this interest such as the attempts to eradicate use of critical race theory and “diversity, equity and inclusion” (DEI). Both of these moves have been accompanied by oversimplified and often false explanations to dissuade the public from questioning the idea that either practice is somehow harmful to them, and unfortunately it seems to have worked pretty well. In reality, the application of either concept can only result in the increased comfort or accomplishment of marginalized groups, which is what national leaders are looking to avoid. Which leads to a question: when a society fights tooth and nail to avoid concepts that can only ultimately manifest in full cognizance, when it actively obfuscates and treats learning as a negative, when it proclaims that introducing our children to this way of thought is dangerous and a threat to our nation, what does it say of that society?

A well educated majority in America would be unprecedented and therefore a massive change that would beget a series of other changes to the system, most of which are unwanted by the system itself; the distribution of power in this country has never been even and the people hoarding it would prefer that it stayed that way. This is a change that fundamentally scares them to even consider, and would come even quicker if the people understood the depth of the ways in which they’ve been wronged–restricting access to information is one of their most consistent forms of manipulating the masses, of maintaining control. In truth, I think the fear is unfounded because it hinges on the belief that the general population would behave with that power in the same way that the corrupt minority has, but that doesn’t change that it’s what the decision makers operate based on. They fear what we would do in their position because they know what they’ve done, but the self interested mindset that results in human rights violations is simply not as widespread as they believe. Minorities of any type do not aim for revenge in our activism, but reparations. Equity, not superiority; not to be revered as gods but just as fully human without hesitation or stipulation.

Like the Panthers, I operate with a functionally complete distrust of this government and its desire to protect and care for its citizens, let alone ability to do so. The dissolution of the Department of Education in conjunction with the aforementioned widespread villainization of inclusion have led me to this conclusion–it’s become crucial once again for us to reference and create our own history, to record our efforts and experiences and most importantly pass on exactly what they don’t want us to. Liberation schools in the form that they existed in the Civil Rights Movement may not be a feasible option anymore but it’s well past time that our education was in our own hands again. With each passing legislation participation in the current system becomes less reliable, so it’s likely that the solution is to create our own once more.

…we know that because the People, and only the People are the makers of world history, we alone have the ability to struggle and provide the things we need to make us free. And we must with love of mankind pass this on to all of those who will survive. For whether we survive as a people depends on what we do today.

The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service Vol. VI No. 9, “huey p. newton intercommunal youth institute”

Sources

- A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States: “The Black Panther Party”, Howard University Vernon E. Jordan Law Library

- “Birth of SNCC”, “Where do we go from here?” and “The Black Panther” by Charlie Cobb for the SNCC Digital Gateway

- Suzanne Collins’ official website

- Photos from the National Museum of African American History & Culture’s collection

- The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes by Suzanne Collins

- Black against Empire by Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr.

- An Oral History With Ericka Huggins by Fiona Thompson

- The Oakland Community School: A BPP Community Survival Program by Erica Huggins

- The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service Vol. VI No. 9, “Huey P. Newton Intercommunal Youth Institute”

Further Reading

Quick Reads:

- A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States: Black Civil Rights, Howard University Vernon E. Jordan Law Library

- “8 Black Panther Party Programs That Were More Empowering Than Federal Government Programs”, Atlanta Black Star

- Revisiting and Learning from the Legacy of Black Communities’ Education for Liberation Efforts, NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools

- The Black Panther Party: Challenging Police and Promoting Social Change, National Museum of African American History & Culture

Longer Investments:

- Ericka Huggins: The Official Website

- Education for Liberation: The Black Panther Schools

- Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom by Heather Andrea Williams

- Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle edited by Dayo F. Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, Komozi Woodard